Legislation frequently involves making classifications that either advantage or disadvantage one group of persons, but not another. States allow 20-year-olds to drive, but don't let 12-year-olds drive. Indigent single parents receive government financial aid that is denied to millionaires. Obviously, the Equal Protection Clause cannot mean that government is obligated to treat all persons exactly the same--only, at most, that it is obligated to treat people the same if they are "similarly circumstanced."

Over recent decades, the Supreme Court has developed a three-tiered approach to analysis under the Equal Protection Clause.

Most classifications, as the Railway Express and Kotch cases illustrate, are subject only to rational basis review. Railway Express upholds a New York City ordinance prohibiting advertising on commercial vehicles--unless the advertisement concerns the vehicle owner's own business. The ordinance, aimed at reducing distractions to drivers, was underinclusive (it applied to some, but not all, distracting vehicles), but the Court said the classification was rationally related to a legitimate end. Kotch was a tougher case, with the Court voting 5 to 4 to uphold a Louisiana law that effectively prevented anyone but friends and relatives of existing riverboat pilots from becoming a pilot. The Court suggested that Louisiana's system might serve the legitimate purpose of promoting "morale and esprit de corps" on the river. The Court continues to apply an extremely lax standard to most legislative classifications. In Federal Communications Commission v Beach (1993), the Court went so far as to say that economic regulations satisfy the equal protection requirement if "there is any conceivable state of facts that could provide a rational basis for the classification." Justice Stevens, concurring, objected to the Court's test, arguing that it is "tantamount to no review at all."

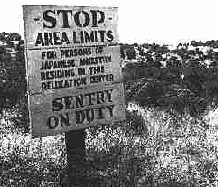

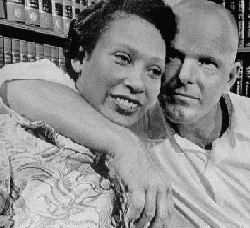

Classifications involving suspect classifications such as race, however, are subject to closer scrutiny. A rationale for this closer scrutiny was suggested by the Court in a famous footnote in the 1938 case of Carolene Products v. United States (see box at left). Usually, strict scrutiny will result in invalidation of the challenged classification--but not always, as illustrated by Korematsu v. United States, in which the Court upholds a military exclusion order directed at Japanese-Americans during World War II. Loving v Virginia produces a more typical result when racial classifications are involved: a unanimous Supreme Court strikes down Virginia's miscegenation law.

The Court also applies strict scrutiny to classifications burdening certain fundamental rights. Skinner v Oklahoma considers an Oklahoma law requiring the sterilization of persons convicted of three or more felonies involving moral turpitude ("three strikes and you're snipped"). In Justice Douglas's opinion invalidating the law we see the origins of the higher-tier analysis that the Court applies to rights of a "fundamental nature" such as marriage and procreation. Skinner thus casts doubt on the continuing validity of the oft-quoted dictum of Justice Holmes in a 1927 case (Buck v Bell) considering the forced sterilization of certain mental incompetents: "Three generations of imbeciles is enough."

The Court applies a middle-tier scrutiny (a standard that tends to produce less predictable results than strict scrutiny or rational basis scrutiny) to gender and illegitimacy classifications. Separate pages on this website deal with these issues.

Do Equal Protection Principles Apply to the Federal Government?Note that the Fourteenth Amendment reads "No STATE shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." Is the federal government thus free to discriminate? Is it possible that women could be denied positions in the Labor Department because of their sex or that West Point could refuse to admit Hispanics? The answer, which is not obvious as a constitutional matter, was provided in Bolling v Sharpe (1954), in which the Court found segregation in the public schools of Washington, D.C. violated the Constitution. Chief Justice Warren wrote:

"The Fifth Amendment, which is applicable in the District of Columbia, does not contain an equal protection clause as does the Fourteenth Amendment which applies only to the states. But the concepts of equal protection and due process, both stemming from our American ideal of fairness, are not mutually exclusive. The "equal protection of the laws" is a more explicit safeguard of prohibited unfairness than "due process of law," and, therefore, we do not imply that the two are always interchangeable phrases. But, as this Court has recognized, discrimination may be so unjustifiable as to be violative of due process. "

No State shall. deny to any person within its

Sign at World War II Relocation Center in California.

Fred Korematsu

"Here is an attempt to make an otherwise innocent act a crime merely because this prisoner is the son of parents as to whom he had no choice, and belongs to a race from which there is no way to resign."--Justice Robert Jackson, dissenting, in Korematsu v United States.

n4 There may be narrower scope for operation of the presumption of constitutionality when legislation appears on its face to be within a specific prohibition of the Constitution, such as those of the first ten amendments, which are deemed equally specific when held to be embraced within the Fourteenth.

It is unnecessary to consider now whether legislation which restricts those political processes which can ordinarily be expected to bring about repeal of undesirable legislation, is to be subjected to more exacting judicial scrutiny under the general prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment than are most other types of legislation.

Nor need we enquire whether similar considerations enter into the review of statutes directed at particular religious, or national, or racial minorities: whether prejudice against discrete and insular minorities may be a special condition, which tends seriously to curtail the operation of those political processes ordinarily to be relied upon to protect minorities, and which may call for a correspondingly more searching judicial inquiry.

Mildred and Richard Loving, who successfully challenged Virginia's miscegenation law. (UPI)